ITL #482 It’s lonely at the top: helping CEOs perform

2 years, 9 months ago

(Comments)

Why do successful Chief Executive Officers experience loneliness, what effect can this have on their performance and that of their organisation – and what should the Communications Director do about it? By Nanne Bos.

Lonely people are perceived as less socially skilled, less achieving and less intellectually competent. None of these characteristics seem to be typical of chief executives, who in general are intelligent, socially and psychologically well adjusted.

Yet, according to many media reports, executive loneliness troubles many successful top executives. A recent study by Harvard Business Review found that 50% of CEOs have performance issues as a result of this. While loneliness is a general human phenomenon, it can develop in such a way that it dramatically impacts executive performance and decision-making and ultimately disrupt the organisation’s equilibrium enough to contribute significantly to its decline. Indeed, it may well be one of the reasons why CEOs fail.

Top executives face significant challenges and are under tremendous pressure to deliver results. Time pressure is enormous as the average CEO tenure continues to decrease, falling from 10 years in 2000 to less than 5 years in 2017. This workload creates extraordinary levels of fragmentation in an organization, which makes it very difficult for the CEO to take the time to get closer to their people and stakeholders. Working closely with senior management, Communications Directors are often among the few trusted advisors of the CEO and serve as the liaison with the various stakeholders.

Gaining a better understanding of the phenomenon of executive loneliness will help communications advisors to help the executive to better cope with it, and ultimately improve the performance of both the executive and the organisations they are managing.

Network of decisions

Every day, CEOs face the relentless task of making decisions – about tactics and strategies, customers and markets, employees, other stakeholders and more. These decisions can vary in significance and complexity, but some have the potential to determine the fate or fortune of a company. And all these decisions are at the basis of social interactions. Organisations are in fact social structures of interacting roles making decisions and taking action from those decisions. Some of these decisions are made consciously with a great deal of thought and consultation with others, some are made out of habit and other decisions are driven by influences outside our awareness.

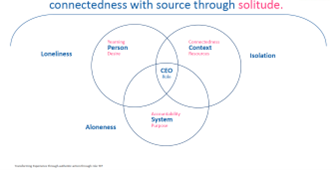

The behaviour and the decisions and the actions the CEO takes are strongly influenced, if not largely determined by influences both internal and external to the executive, of which he or she is not always aware. Understanding executive loneliness means that we must not only observe it from an outside perspective: more importantly, we need to understand those influences that are largely outside our awareness. The Transformation Experience Framework (TEF), a model developed by the Grubb Institute, offers a dynamic model to explore the phenomenon. The framework explores how people can take action through taking up a certain role at the intersection of four domains of experience. The experience of being a person (psychological), the experience of being in a system (organisation), the experience of being in a context (social, economic, political), and the experience of connectedness with the spiritual domain, the domain of deeply held values.

Executive loneliness centres on the CEO role because it is within this role that decisions can be made and actions taken. However, looking at the CEO as the centre of all things should be challenged. The limited research surrounding executive loneliness tends to focus almost exclusively on personal characteristics as the primary determinant of the experience, and largely ignores context, leader-follower and stakeholder relationships as a potential cause. As such, personality tends to be overestimated and hardly any attention is given to external and organizational factors, such as culture, corporate life cycle, social support or person-organization fit.

Persons in the CEO role are subject to pushes and pulls of forces well beyond them, forces that originate in systems and contexts. To understand executive loneliness we must therefore look outside in, seeing the group and the context first.

To understand executive loneliness, it is paramount to start by exploring the constructs of loneliness, solitude and isolation.

The essence of loneliness

Loneliness is a universal human experience that can affect anyone. For some, it is always there; for others, it is short-lived. There are many definitions, but they all have some things in common: loneliness is a perceived lack of closeness to others; a perception of oneself as being isolated or alone. Loneliness is a painful, profound experience and emotion, and it affects individuals’ mental and physical health, as well as their relationships in general. It gives a sense of pain or sadness that is related to a wide range of emotions, including poor mood, anxiety, anger, optimism, low social support and lower self-esteem. Loneliness functions as a warning signal. Similarly to how physical pain protects us from physical dangers, social pain urges us to strengthen the social network needed to ensure survival and promote social trust, cohesiveness and collective action.

The first recorded use of the word ‘lonely’ in English occurs in Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, where it is used to indicate the state of utter aloneness. This may lead to the idea that loneliness and aloneness are synonymous: indeed, there seems to be a widespread idea that lonely people are more alone, and those alone lonelier. However, loneliness is independent from aloneness, as it is basically a numerical and physical term that indicates nothing beyond the fact that a person is not surrounded by others. How people experience and react to being alone can vary considerably, all the way from an ‘oceanic feeling’ to a feeling of sadness.

Whereas loneliness expresses the pain of feeling alone, solitude expresses the beauty of being alone. It is a state in which we disengage from the immediate demands of others and are free to choose our mental or physical activities.

Leadership requires independence and vision, necessitating the opportunity for executives to be alone with their thoughts. This is increasingly important when executives face increasingly complex demands. Solitude helps to allow executives to reflect on all aspects of the organization and its challenges. However, because solitude requires temporary withdrawal from social interaction, it potentially increases social disengagement from the demands and expectations of others.

Throughout history, solitude has proved a very powerful source of inspiration for many leaders (including spiritual leaders) and artists. Jesus, Mohammed and the Buddha sought solitude and returned to share their discoveries with others. Many philosophers have emphasized solitude as something positive: a privileged space of reflection in which one can get particularly close to the truth.

This leads to the question of what happens to individuals when they climb the ladder of success. Is loneliness of command caused by the executive’s personality or triggered by role-related, organizational and contextual factors?

Understanding executive loneliness.

As soon as the executive is appointed as CEO, the social network of mutual dependencies of peers and subordinates in that organization changes drastically. To facilitate ‘neutrality’ in decision-making, relationships need to be redefined and more distance has to be kept. While executives may be able to temporarily satisfy their followers’ dependency needs, they have to cope with the frustration of their own needs. These dynamics can further fuel and perpetuate loneliness.

The executive’s appointment and subsequent change in the social system may also cause close peers and colleagues to become reluctant to share relevant information about what is really going on in the organization. In the back of their minds, they are aware that, from that point on, the top executive has decision-making power over them: their promotions, salary increases, etc. As a result, they too want to keep some distance, further increasing the risk of isolation.

Being a CEO of a stock-listed company means being exposed to a great deal of attention from both external and internal stakeholders. All demand the CEO live up to an image that, in most cases, is pre-established. To maintain public confidence, CEOs may create the illusion that they need no one and reinforce this image by projecting that they are competent, in control and confident in the future. These factors may put pressure on the genuineness of the executive and raise the question of whether he or she wants and can live up to those expectations. As the good of the company is often put first, these dynamics can evoke a sense of alienation or self-estrangement from aspects of their personality, triggering a feeling of loneliness.

Within the organization, the image of the perfect leader also has an effect, as the executive may become the target of his or her employees’ projections. For example, employees may start to idealize the CEO to recreate the sense of security and importance they felt in childhood when they were cared for by omnipotent parents. As a result, they allow the CEO to operate in isolation, which can eventually lead many executives to lose a firm grasp on reality and the ability to distinguish fact from fantasy – splitting their world between those ‘with’ them and those ‘against’ them, and surrounding themselves with people who reinforce this fantasy. This transference onto the leader adds to his or her stress and eventual isolation.

Personality

The degree to which a top executive is impacted by loneliness is highly dependent on his or her personality. Personality is achieved through a complex process of psychological and physical development. According to a recent study by Korn Ferry, the average age for CEOs is 58. This means that by the time the executive reaches the top, he or she has gone through a long and enduring process of development in personhood, emotionally, intellectually, physically and in terms of relationships.

Personality is impelled by both desire and yearning. Psychoanalysis has extensively demonstrated the power that conscious and unconscious desires have on our behaviour and our conscious experience. Less discussed is the idea of yearning. Yearning is the experience of deep and extensive longing. Yearning in psychological terms, is established through the process of sublimation, where desire becomes linked to a purpose beyond the ego. It is about finding meaning, values and identity within a purpose beyond the self.

Desires

CEOs face increased expectations to engage with employees and stakeholders to advance the organization. These expectations tend to favour extraverts in leadership roles. Extraversion is characterized by excitability, sociability, talkativeness, assertiveness and significant emotional expressiveness. Highly extraverted people are outgoing and tend to be energized by social situations. Introverted people tend to be more reserved and have to expend energy in social settings. People often assume that executives who rate high on extraversion are less likely to be lonely. Yet being well connected and highly sociable does not preclude loneliness. Equally, executives who score low on extraversion might be perceived as lonely, but may actually feel less lonely as they have a stronger preference for solitude. For a communications director it is key to understand this personal trait of the CEO, as introverted and extraverted leaders face different communication challenges and require different approaches.

Another key personality trait in this context is narcissism. A healthy dose of it is essential for human functioning, and leadership and narcissism are well connected. Narcissism is defined by grandiosity, interpersonal exploitativeness, empathic difficulties and a sense of entitlement. Some argue that these times require narcissistic leaders who are skilled orators and creative strategists, and who have a great ability to inspire followers – the so-called superstar CEOs. Others argue that excessive narcissism is one of the causes of executive loneliness, as it fuels the leader’s isolation. Indeed, narcissists seem to view social relationships as a vital element of self-construction and this brings the risk of becoming isolated from reality and falling victim to the cycle of grandiosity. When dealing with these type of personality traits, the capability of the communications director to remain independent is key to remain effective. Staying outside the bubble, and confronting the leader with a realistic outside-in perspective is paramount.

Yearning and solitude.

For a top executive to exercise power, one must feel secure in one’s individuality, one’s sense of self and one’s sense of direction and purpose. This seems to play a major role both in fuelling a sense of loneliness and in dealing with it. That is to say, maintaining the delicate balance between individual independence and oneself as a genuine member of the corporate group is essential to one’s ability to perform leadership and management tasks. Some executives confirmed that, as CEO, you are required to remain independent and make decisions that are in the best interests of the organization. Keeping in touch with that sense of purpose allows executives to better navigate their loneliness.

System and context

The organisational system has its own culture, language and rules. It provides the role for the CEO but also the expectations that come with the job. The system influences, helps and limits the CEO in his endeavours. The rules and cultural patterns of the system, both conscious and unconscious, play an important role in the pushes and pulls to which the CEO is subject. Systems have a purpose and as a result, the experience of being in a system brings forward the tension between personal needs and desires and those of others. And this plays a major role in the experience of executive loneliness.

Once the CEO is appointed, new networks emerge. In particular, relationships with fellow executive and non-executive board members may play an important role in increasing or reducing executive loneliness. Clearly a healthy balance between the respective powers of the CEO and the executive and non-executive board members is required to ensure effective company performance. But what is a healthy balance, and how does this impact the CEO’s sense of loneliness?

The non-executive board members seem to have two conflicting tasks with respect to the CEO. The first is to monitor the CEO’s managerial activities and to protect ownership interests, which may be impaired by the CEO’s pursuit of self-interests. The second is to provide counsel to the executive. The combination of these tasks often leads to ‘an uneasy but more coequal alliance’.

While the board members’ roles in corporate governance have attracted much academic attention, less attention has been given to the psychodynamic perspective. As members of the human species, we have no choice but to be part of a group or groups. This creates a paradox. We each need to retain and express our feelings of separateness, individuality and independence, while at the same time needing to feel ourselves part – an accepted member – of the group. But the group’s needs, attitudes and feelings often run contrary to our own. To exercise power, one must feel secure in one’s individuality and sense of purpose. However, exposing oneself to that extent immediately threatens one’s position as a member of the group, and probably increases one’s feelings of loneliness.

Context

The context is the environment within which an organisational system occurs. The environment includes the physical, political, economic, social, international and emotional context for a system. What is happening in the context will have an effect on persons, organisations and social systems. It is the context that often triggers a crisis – that puts pressure on the system and the CEO. If things become unbalanced due to changes in the organization’s competitive context, the feeling of loneliness may occur.

Implications for Communications Directors working with CEOs:

Get close

The main task of a Communications Director is to help the CEO and senior leadership to engage with their internal and external stakeholders. This can only be effectively done, if the Communications Director has a clear understanding of what is going on amongst external audiences, within the organisational system but more importantly what motivates and works for the CEO from a personal and role perspective. This means that the Communications Director often gets in a very close relationship with the CEO. Having a deep understanding of both the personal desires and characteristics of the CEO is key to protect the executive from isolation and help the executive communicate more effectively with stakeholders.

Tap into the power and vision

Leadership requires vision. And vision requires the leader to be alone with his or her thoughts. Communications Directors should help in creating the mental space that is necessary for the CEO to develop his or her vision. Moreover, Communications Directors play a crucial role in communicating the strategic vision and making sure that both internal and external audiences are engaging with it. A vision often is related to the strategic challenges the organisation has. However, it is more powerful to understand the yearning of the CEO and use his personal purpose to connect to a broader audience.

Connect

The Director of communications is tasked with building relationships within and without the business. The Director establishes meaningful relationships externally with consumers and media, consumer forums, and on social media platforms. A similar approach is often developed for internal audiences. As the executive’s appointment as CEO and subsequent change in the social system also causes peers and former colleagues to become reluctant to share information about what is really going on in the organisation, it is the task of the Communication Director to not only become the trusted advisor of the CEO, but also stay well connected to the informal flow of information and senior management layers. This often also includes the other executive and supervisory board members.

Coach & Manage

Who can you trust once you have reached the top? A Communications Director can only be effective if he or she has the full trust of the CEO. The more the CEO will trust the Communications Director, the less lonely he or she will become. Sharing his or her doubts will put the Communications Director in the role of coach and can help to improve the performance of the CEO. Trust is necessary to help the CEO to use his or her vulnerability to re-engage with stakeholders.

Independence

Every CEO runs the risk of becoming isolated from reality and falling victim to a cycle of grandiosity. It is key for the Communications Director to get close but to stay out of this cycle. And that is easier said than done. For this the Communications Director needs to manage his or her own loneliness.

The highest performance is reached only as the executive remains independent in his or her advice and is capable of observing the CEO (both from a personal and role perspective) in the context and system. Getting personally close to the CEO can potentially compromise the neutrality of advice and as a result make the relationship dysfunctional. This is something the Communications Director should keep in mind at all times.

About the author

Nanne Bos is currently the Chief Communications Officer at Aegon Group. As he got more and more involved in organisational change, he decided to go back to University to gain a deeper understanding of individual and organisational change. Having observed the phenomenon of executive loneliness in a number of occasions throughout his career, he decided to research the phenomenon for his thesis.

The Author

Nanne Bos

Nanne Bos is currently the Chief Communications Officer at Aegon Group. As he got more and more involved in organisational change, he decided to go back to University to gain a deeper understanding of individual and organisational change. Having observed the phenomenon of executive loneliness in a number of occasions throughout his career, he decided to research the phenomenon for his thesis.

mail the authorvisit the author's website

Forward, Post, Comment | #IpraITL

We are keen for our IPRA Thought Leadership essays to stimulate debate. With that objective in mind, we encourage readers to participate in and facilitate discussion. Please forward essay links to your industry contacts, post them to blogs, websites and social networking sites and above all give us your feedback via forums such as IPRA’s LinkedIn group. A new ITL essay is published on the IPRA website every week. Prospective ITL essay contributors should send a short synopsis to IPRA head of editorial content Rob Gray emailShare on Twitter Share on Facebook

Comments